One type of public record that can be very useful for family history research is a census record. Taking a census is a government’s method of counting the country’s population. Censuses have been taken since ancient times. The scope of this article will be limited to the United States census. While census records can be very useful for genealogists, they were created for the purpose of counting people for the purpose of taxation and political representation. As a result, the questions that genealogist seek to answer were not always asked. Censuses have been conducted every ten years in the United States beginning in 1790.

One type of public record that can be very useful for family history research is a census record. Taking a census is a government’s method of counting the country’s population. Censuses have been taken since ancient times. The scope of this article will be limited to the United States census. While census records can be very useful for genealogists, they were created for the purpose of counting people for the purpose of taxation and political representation. As a result, the questions that genealogist seek to answer were not always asked. Censuses have been conducted every ten years in the United States beginning in 1790.

Censuses can be very valuable in locating where your ancestors lived during the census year. The census record provides “a snapshot” of the person’s family and living situation. However, because of possible inaccurate information contained in them, they should not be your only source of information unless there is no other source of information available. They were conducted by people who were working on a quota system which meant quality sometimes suffered for the sake of quantity. Some census takers jotted down notes as they talked to people, then took the notes home where they might be transcribed onto the official forms by a wife or older child. Census takers used ditto marks liberally. A friend shared with me a census report in which her Caucasian ancestors had been reported as being black. Turns out they were the only white family in an otherwise black neighborhood and the census taker used the ditto marks a bit too liberally! Information was also sometimes gathered from other people in the neighborhood about households where no one was home when the census takers came by. There were times and places in US history when immigrants were not welcome whether the person was from a different country or different state. For this reason, if you are able to find your immigrant ancestor in several different census years, the place of birth may vary from one census to another. I don’t mean to discourage you from looking for your ancestors in the census because they can be a great tool. Just in mind the limitations of the census records in case you encounter conflicting information.

As this cartoon illustrates, the questions that genealogists are happy the census takers asked may have seemed intrusive to our ancestors. Our ancestors being uncomfortable with the questions may at times have affected the answers given.

When selecting a census to search, start with the most recent one in which your ancestor might have appeared. In the United States, there is a 72 year privacy limit for viewing the census. As a result, the most recent US census available for searching is 1940. More recent censuses contain more information which might be helpful in finding your ancestor on an older census.

This is a summary of the information that can be found on the various years of the US census as found at: https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/index_of_questions/ Bulleted point information in this article was taken directly from the website.

1790-1840: These early censuses were only a head count that identified the head of household and the number of people in the household, both slave and free.

1850: This was the first census to list all the inhabitants of the household. It also listed for each member of the household:

-

their age

-

sex

-

color (race)

-

profession of each person over 15 years old

-

value of real estate

-

place of birth

-

if the person was married within the past year

-

in school during the past year

-

if over 20 years, could the person read and write

-

was the person “deaf, dumb, blind, insane, idiotic, pauper or convict.”

With all the details it did list, it unfortunately did not identify the relationship of members of the household to each other. The 1850 census also included a slave schedule that listed the owner’s name and the number, age and gender of slaves but not their names.

The 1860 census includes the same information as 1850.

The 1870 census contained the same questions as the previous two censuses with these additional questions:

-

Was the person’s father of foreign birth?

-

Was the person’s mother of foreign birth?

-

If the person was born within the last year, which month?

-

If the person was married within the last year, which month?

-

Is the person a male citizen of the United States of 21 years or upwards?

-

Is the person a male citizen of the United States of 21 years or upwards whose right to vote is denied or abridged on grounds other than “rebellion or other crime?”

The 1880 census was the first to identify each person’s relationship to the head of household. This is important information when, for example, there are children in the household who might sons and daughters, grandchildren or nieces and nephews. Other additional questions asked for the 1880 census included:

-

Is the person single, married, widowed or divorced?

Enumerators were to mark “W” for widowed and “D” for divorced

-

What was the person’s father’s place of birth?

-

What was the person’s mother’s place of birth?

Census questions are also deleted from one census to another. The 1870 questions regarding the month of birth if born during the previous year and month of marriage if married during the previous year were not included in the 1880 census. Also absent were the questions regarding citizenship and voting rights for males over 21 years old.

The 1890 census was destroyed by fire with only fragments of its records remaining. Some states took their own censuses between the federal censuses in years that ended in 5, for example, 1885. State census when available can be used to both supplement the federal census and to help replace the 1890 census.

The 1900 census included some new questions that can be very helpful for genealogical research. These questions include:

The 1900 census included some new questions that can be very helpful for genealogical research. These questions include:

-

Month and year of Birth (1900 is the only census that includes this information.)

-

How many years has the person been married?

-

For mothers, how many children has the person had?

-

How many of those children are living?

-

What year did the person immigrate to the United States?

-

How many years has the person been in the United States?

-

Is the person naturalized?

-

How many months has the person not been employed in the past year?

-

Can the person speak English?

-

Is the person’s home owned or rented?

-

If it is owned, is the person’s home owned free or mortgaged?

-

Does the person live in a farm or in a house?

If a person lived on a farm, the enumerator was to write that farm’s identification number on its corresponding agricultural questionnaire in this column

The 1900 census also included an Indian (or Native American) schedule which included the following questions:

-

Indian Name

-

Tribe of this person

-

Tribe of this person’s father

-

Tribe of this person’s mother

-

Fraction of person’s lineage that is white

-

Is this person living in polygamy?

-

Is this person taxed?

An American Indian was considered “taxed” if he or she was detached from his or her tribe and was living in the White community and subject to general taxation, or had been allotted land by the federal government and thus acquired citizenship. -

If this person has acquired American citizenship, what year?

-

Did this person acquire citizenship by receiving an allotment of land from the federal government?

-

Is this person’s house “movable” or “fixed?”

Enumerators were to mark “movable” if the person lived in a tent, tepee, or other temporary structure; they were to mark “fixed” if he or she lived in a permanent dwelling of any kind.

The 1910 Census including the separate Indian schedule is essentially the same as the census taken in 1900. An additional question of interest to genealogist: Is the person a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy?

The 1920 census was the first to give the street address of the household. It asked the year of naturalization if the person was a naturalized citizen. The 1920 census is the only census to include the year of naturalization. It also included questions about the person’s “mother tongue” and the “mother tongue” of the person’s mother and father. Otherwise, the questions were similar to the previous census. There was no separate Indian schedule. Native Americans were included in the general census with all other Americans.

The 1930 census included a change concerning how race was classified. Gone is the classification of mulatto. A person with any Black heritage is reported as being Black. New questions asked in the 1930 census include:

-

Does this person live on a farm NOW?

-

Did this person live on a farm A YEAR AGO?

-

Whether the person is a veteran of the U.S. military or naval forces mobilized for any war or expedition?

-

If yes, which war or expedition?

Enumerators were to enter “WW” for World War I, “Sp” for the Spanish-American War, “Civ” for the Civil War, “Phil” for the Philippine insurrection, “Box” for the Boxer rebellion, or “Mex” for the Mexican expedition.

The 1930 census was taken after the Great Depression had begun and so included additional questions to be asked if a person of employable age reported that they were currently unemployed. The separate schedule for Native Americans was again part of the 1930 census.

The 1940 census was the first census designed to take a statistical sample. The form can be a little confusing to read because it includes columns that the census takers left blank and were filled in as the statistics of the census were calculated. The statistical columns have the word CODE at the top of them, so ignore those columns unless you want to dig into the meaning of those columns. If you do have an interest, the information is available on the Internet. One code I do know that will be generally helpful is a “7” beside the “M” for married which means that only one of the two spouses was currently living in the household at the time of the census. Another first for the 1940 census is a way to know who in the household answered the census taker’s questions. Look for a circled X next to a person’s name. The circled X indicates the person who gave the census taker the information. The United States was still suffering from the Great Depression in 1940 and the questions reflected the government’s concern about the rate of unemployment.

New to the 1940 census were these questions:

-

Value of the home, if owned, or monthly rental, if rented

-

Did the person attend school or college at any time in the past year?

-

What was the highest grade of school that the person completed?

-

In what place did the person live on April 1, 1935?

For persons 14 years and older – employment status -

Amount of money, wages, or salary received (including commissions)

-

Was the person at work for pay or profit in private or nonemergency government work during the week of March 24 – 30?

-

If not, was he at work on, or assigned to, public emergency work (WPA, NYA, CCC, etc.) during the week of March 24 – 30?

-

If the person was neither at work or assigned public emergency work: was this person seeking work?

-

If not seeking work, did he have a job or business?

-

For persons answering “No” to questions 21, 22, 23, and 24; indicate whether engaged in home housework (H), in school (S), unable to work (U), or Other (Ot)

-

If the person was at work in private or non-emergency government employment: how many hours did he work in the week of March 24 – 30?

-

If the person was seeking work or assigned to public emergency work: what was the duration, in weeks, of his unemployment?

For the 1940 census, the census taker was to ask additional questions of two people chosen at random. The people chosen for the additional questions appear at the bottom of the census page. Be sure to look at the bottom of the page that your ancestor appears on to see if they were chosen for the additional questions.

Whenever possible obtain a copy of the actual census image so that you can see all the information that the census contains about your ancestors. All the information on the census can be used as clues to find other records and for knowing more about your ancestor’s life. For example, I learned from the 1940 census that my father at age 20 was a service station attendant which I didn’t know before viewing the census. The 1940 census also includes the information that my father’s parents’ home was worth $2000 and was mortgage-free and his father’s income was $2400 per year. That suggests to me that my grandparents were good money managers. I love finding this kind of detail about my family members! If I have included some much detail about the census that your eyes are glazing over, I hope you will find the details useful when you are looking for your own ancestors in the census.

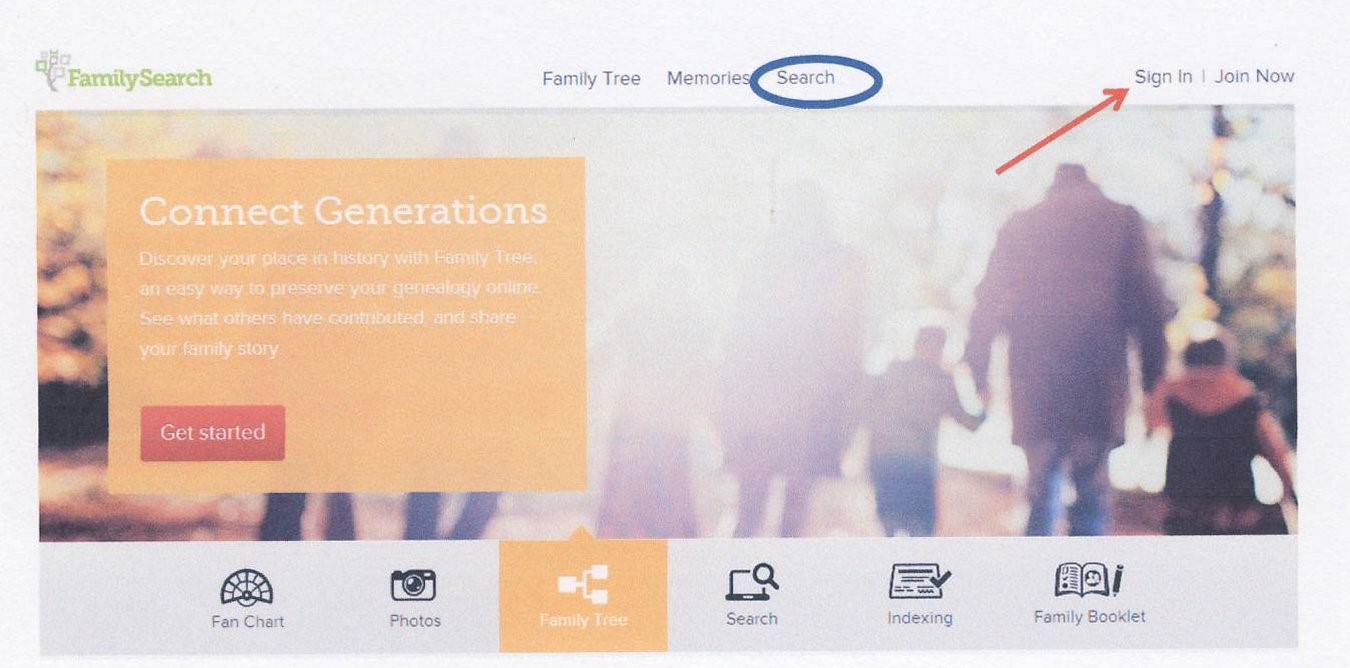

Ancestry.com provides the best access to the US census and includes the ability to view and download the actual census images. If you don’t have an Ancestry.com subscription; go to your local Family Search Family History Center or your public library. FamilySearch.org has some of US census records and your ability to view them will be improved if you sign in with your free Family Search account. Both Ancestry and Family Search have some of the state censuses also.

About Christine Bell

Christine Bell has been seeking her ancestor for almost forty years and continues to find joy in each one she finds. She volunteers in a Family Search Family History Center where she helps others find their ancestors. As a convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Saints, she is grateful to be a member of the Church. She is a wife, mother of six grown children, grandmother of five going on six, and currently living in the western United States. Christine enjoys spending time with family and creating quilts for family, friends and Humanitarian Services of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I love the stories in census records. I was following one ancestor and found she had two children out of wedlock who were raised by their father. In one census, after the boys went to their dad, she moved in with her brother, who had a live-in housekeeper. The housekeeper had a young daughter. The next census showed, to my surprise, that he’d married the housekeeper and adopted the daughter. I wondered how my ancestor felt about that. Then my ancestor disappeared from the census records, so I went looking for a death certificate. That led me to discover that somehow she wound up back where she was born, paralyzed, died, was buried by her neighbors, and a year later, someone in town got around to getting her death certificate. It was like reading a novel, following her through those census records.

Thank you for sharing this story. I have found that sometimes just one census record tells a story. I found a family in which the father had immigrated to the US 5 years before his wife and children, that’s a story of struggle.