After I heard from both the doctor and a geneticist that my baby would be born with Down syndrome I paged my husband to call home. He was away on business and would know that the page meant the results had come in. Calling from a pay phone at Union Square in San Francisco, he said “Before you tell me, I have to say that I am hoping it is Down syndrome.” “Well, you’re way ahead of me,” I said. Knowing that this diagnosis meant coming to grips with a pretty big and entirely new reality, I had thought I might not choose it if I had a choice, so I asked him “Why would you say that?” He answered that he’d been thinking about it and talking around with people and he said “I’ve heard what it does for the other children.” He said he’d heard that the siblings of a handicapped child come away with some great skills and emotions and perspectives that were assets unique to people with that experience. It’s been almost 20 years now; is that true? Do my other children have a handful of knowledge that they couldn’t have gotten in any other way?

I wondered at the time, how is it that they learn these things? If this is true, what is it that teaches them? I think that the answer to those questions is: just the slow beat of time. Something happens in the steady drip of accommodating the necessities of life in a place where one person always wins. Where you hear repeatedly: “He can’t understand what you want.” and “He doesn’t know that that’s hurting you.” You can’t have any expectations of that person who is directing things, and there is no deadline to look toward for when you will have, so one of the things a sibling might have an enhanced opportunity to learn is to “let it go”.

I wondered at the time, how is it that they learn these things? If this is true, what is it that teaches them? I think that the answer to those questions is: just the slow beat of time. Something happens in the steady drip of accommodating the necessities of life in a place where one person always wins. Where you hear repeatedly: “He can’t understand what you want.” and “He doesn’t know that that’s hurting you.” You can’t have any expectations of that person who is directing things, and there is no deadline to look toward for when you will have, so one of the things a sibling might have an enhanced opportunity to learn is to “let it go”.

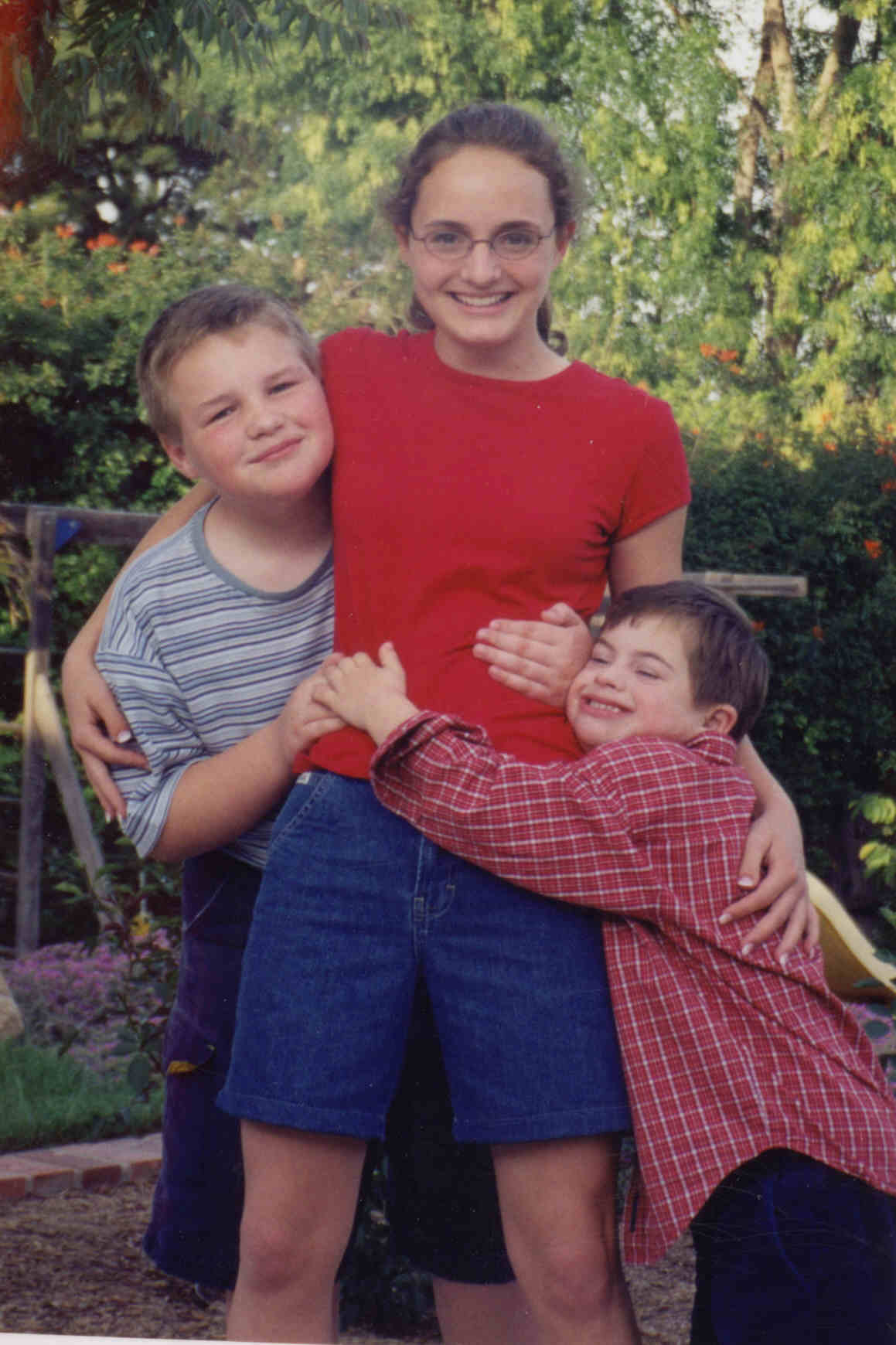

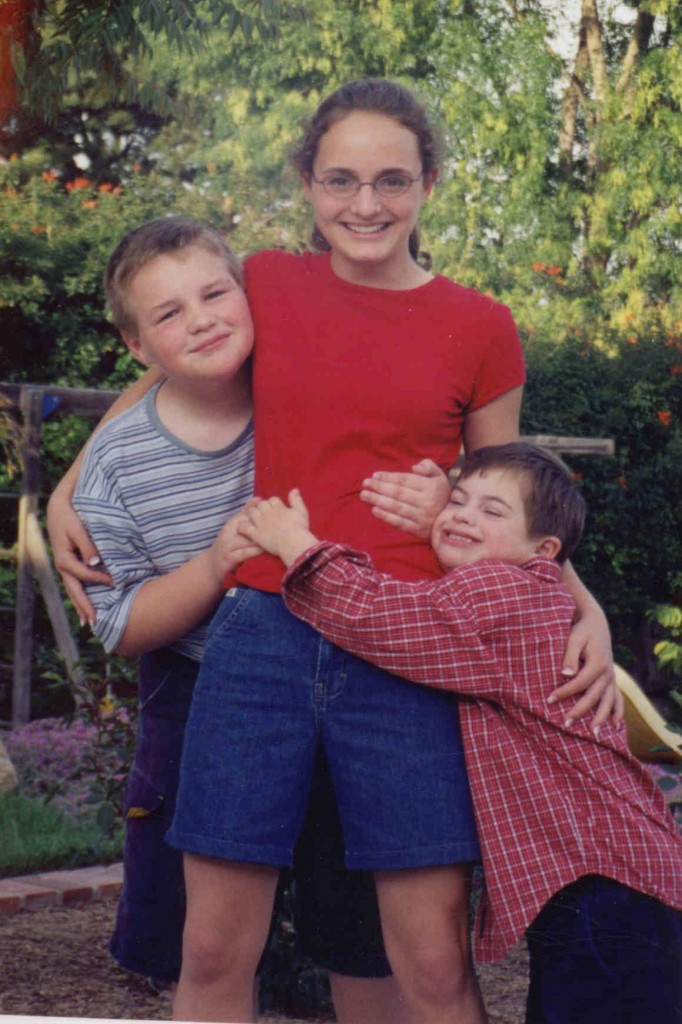

But when the person you have accommodated so many times looks at you as the axis around which their world revolves, and when that person never fails to kiss your cheek so hard you think your jaw might break, or when your name is one of the only few words that he knows and your presence is all that has ever given him the security to smile . . . When you know that your approval is his sunshine, when you might randomly hear him calling from a distant room “Sissy, you cute!” or contentedly murmur “Myyyyy brother” as you walk by, there’s a love that you can’t help but give back.

Whose love is more pure? The child who is innocent and loves because nothing else exists, or the one whose days are complicated and accepts the challenge to love anyway?

. . . That child who can never win because the other side has no idea that there are winners and losers in a struggle of wills? This brother who hears “Steve could you just always sit in the back seat so we don’t have to argue about this every time?” . . . and who freely sacrifices again, and again, and again – in a thousand ways?

. . . Is it that sister whose neat and tidy room is totally trashed – drawers upside down, mattress on the floor, linens here and there, each pair of shoes and earrings . . . one in one corner and one in the other, taking three of us till deep into the night to clean it up? What was that crazy event that took him less than 15 minutes to accomplish? We’ll never know, it was a one-time thing. (Thankfully! He’s never done anything even close to it in the ten years since.) She stood in the doorway sobbing, we were silent in disbelief, and yet she loved him still.

There is absolutely no sense in amassing a burden of emotional baggage that can never be unloaded, so self-preservation mandated that these siblings have the capacity to “let go” without harboring resentment. But did their experiences give this to them, or was it always with them and these experiences just forced them to find it?

When my first son was born my daughter was impatient to eat her breakfast before the baby but I explained to her that the baby didn’t know how to wait and she did, so the baby would have to go first. After breakfast the next day, dressed and ready to go – she said “Mom, you know when I have to wait for you to feed the baby?” “Yes” “Then I know how much I love Stephen.” Throughout eternity I will be able to hear those words as she said them – that sweet little girl, as I would find her doing so many times in the future, making my life easier by her reasonable attitudes. So before she had a handicapped brother, she apparently already knew how to love in the face of personal sacrifice.

When my first son was born my daughter was impatient to eat her breakfast before the baby but I explained to her that the baby didn’t know how to wait and she did, so the baby would have to go first. After breakfast the next day, dressed and ready to go – she said “Mom, you know when I have to wait for you to feed the baby?” “Yes” “Then I know how much I love Stephen.” Throughout eternity I will be able to hear those words as she said them – that sweet little girl, as I would find her doing so many times in the future, making my life easier by her reasonable attitudes. So before she had a handicapped brother, she apparently already knew how to love in the face of personal sacrifice.

Perhaps for a sibling, having the opportunity to practice choosing to give and receive love without expectation, repeatedly and on an extended basis, helps that ability to travel more naturally out of innocent childhood and into their adult lives. If this is so then my husband was wise to wish it for them. Others have told us that they see this type of love in our older children for their brother. The future will tell I suppose if they can carry it over into their broader worlds. I know my world is a better place for who they are, whatever the reason. Thankfully they’ve given me the same wide margin for error and eyes full of forgiveness that they have had for that once-little one who has pretty much been setting the pace all these years.