When my Down syndrome son was born, agency people and programs came rushing at me. One phrase kept being repeated: “You have to be his advocate”. “Yea, right!” I thought. “How can I go to battle for him when I don’t even understand what all these options are that you’re reciting? I don’t know how to find out what he needs. And I don’t know how to best deliver what he needs even if I knew what it was!”

I’ve thought about that directive so many times over the years. I felt it put a lot of pressure on me because – shouldn’t an advocate know what they are talking about? I went to all the meetings. I heard what the experts said. But it was so often in such jargon language that by the time they got to where they wanted my assent or opinion, I might be only barely able to ask an intelligent question. Let alone weigh alternatives or devise an optimal plan. Then I’d think “but I have to be his advocate”, so I’d make my best guess and keep moving.

I’ve thought about that directive so many times over the years. I felt it put a lot of pressure on me because – shouldn’t an advocate know what they are talking about? I went to all the meetings. I heard what the experts said. But it was so often in such jargon language that by the time they got to where they wanted my assent or opinion, I might be only barely able to ask an intelligent question. Let alone weigh alternatives or devise an optimal plan. Then I’d think “but I have to be his advocate”, so I’d make my best guess and keep moving.

I understood the word “advocate” to mean that I should firmly designate which out of many paths was appropriate for my son and then make sure he was allowed to go down it. I had no training to qualify me to choose teachers or curricula. I wasn’t able to predict how any given program would affect him. With all of their background and testing, wasn’t there somebody who could just tell me what to do? That was the trouble. There were too many people and too many possibilities of what to do.

I hardly feel any more educated today about “the system” or available programs established for handicapped children than I did the day I started learning 21 years ago. I can say that they are innumerable and it is impossible to personally check out every one. I’ve taken word of mouth from moms and recommendations from experts. Each time using as my baseline what I thought my son would enjoy.

I didn’t tell anybody this because I thought they expected me to be using facts, figures and research to make my decisions. But facts, figures and research can make your head spin! I’d look at what they were going to be doing and just ask myself if he would enjoy doing that. If so, we’re in. If not, we’re out. Not very scientific, so I kept my method secret and merely affected an authoritative air once I’d made my choice.

I didn’t tell anybody this because I thought they expected me to be using facts, figures and research to make my decisions. But facts, figures and research can make your head spin! I’d look at what they were going to be doing and just ask myself if he would enjoy doing that. If so, we’re in. If not, we’re out. Not very scientific, so I kept my method secret and merely affected an authoritative air once I’d made my choice.

It wasn’t until high school that an unwitting teacher validated that my way of calculating was okay.

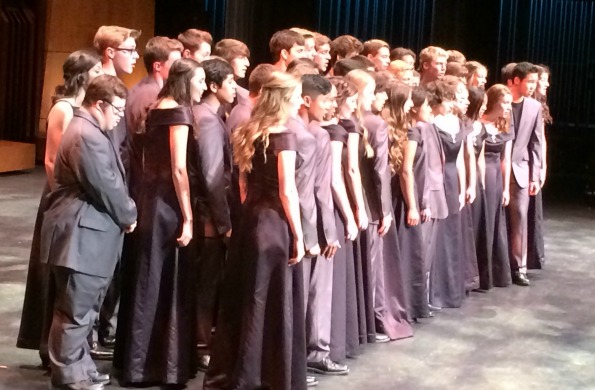

Joey had been in high school a couple of years when we were once again faced with planning for his future activities. I knew he would enjoy being a part of the school choir but, given that he doesn’t speak in public, I didn’t think he would be likely to sing either. And if he did, to what level of success? Enrollment in the choir class was normally by audition only. I wasn’t at all sure that the teacher would welcome him.

Nonetheless as his current teacher and I were going through things I haltingly mentioned choir as an option. He looked at me with surprise and said “Choir??” Of course his response was based on facts, figures and observation. He had only rarely heard any sound come out of my boy’s mouth in the two years he’d been teaching him. It makes sense that choir would never have crossed his mind.

I wasn’t bold, but with my little “advocate” commission pushing me on, I ventured: “Yea, he’d think it was fun.” Instantly he exclaimed: “Well if Joey would think it’s fun, let’s do it!” Now I was the one surprised . . . was it as simple as that for the teacher too?

I wasn’t bold, but with my little “advocate” commission pushing me on, I ventured: “Yea, he’d think it was fun.” Instantly he exclaimed: “Well if Joey would think it’s fun, let’s do it!” Now I was the one surprised . . . was it as simple as that for the teacher too?

Had I been letting the evaluations and reports drive me into hiding for no reason? Is that all the data and studies came down to . . . just fancy ways of analyzing what a person might enjoy? Because I can do that for my son!

I may not know the percentage of Down syndrome folks who meet certain levels of achievement, or what milestones appear at various IQ levels. I don’t even know the developmental stage at which a person should be able to hop on one foot for however many number of times. But I do know what will engage my son’s mind, and I do know what makes him feel happy or proud.

Joey had such a terrific time in that choir! He felt very much “one of the kids”. The other students were tremendous to him, and it thrilled him to perform where he’d seen his brother and sister participate before him. These are things the teacher couldn’t have known. He wasn’t aware that Joey already knew a number of other choir members. He wouldn’t have known that he’d heard the applause his siblings experienced. No amount of clinical assessments could have told him that it would be bliss for Joey to be under the lights on stage with the group rather than be intimidating.

There are no profiles and no evaluations that take into account the total world a child lives in. That’s something only moms and dads can offer. So, come to find out, without any book-learnin’ I had been able to be my son’s best advocate all along. I guess I didn’t know when I’d been up late at night lo these many years that I was studying, but apparently I was. And life is an excellent teacher.

There are no profiles and no evaluations that take into account the total world a child lives in. That’s something only moms and dads can offer. So, come to find out, without any book-learnin’ I had been able to be my son’s best advocate all along. I guess I didn’t know when I’d been up late at night lo these many years that I was studying, but apparently I was. And life is an excellent teacher.

We’ve actually taken him out of school now. The paperwork given to me at the latest meeting showed that he had been sleeping 50% percent of the school day, either at his desk or on the floor. I said “If he’s asleep half the day – he’s bored!” Truthfully, that’s something this teacher couldn’t have known either. Joey wouldn’t have told him, nor would he have made trouble behaviorally. I’d totally expect that if bored, he’d simply check out. And he had been.

My husband and I considered long and hard before making the decision. At last concluding that the program wasn’t a fit, so we pulled him. Let me state here that I’ve taken heat for that verdict from some whom we’ve known for decades. But I no longer search for a shadow in which to deliberate while making up my mind about my son’s care. When one woman let loose with her opinion, shook her head at me and said “I’m chastising you!” Without hesitation, I gave it right back to her, saying with a smile, “Oh, I know you are! But I don’t have to justify myself to you.”

I’ve come a long way baby! That’s probably good because we’ve still got a long way to go. There’ll be many more programs and many more decisions before we’re through.

For now, this is like being on a sweet vacation. We spend our days doing just what we want to do, which includes a considerable amount of Pokémon Go and his usual prodigious artwork. No deadlines, no bus schedules, and my son is supremely contented and happy.

My Down syndrome son’s emotional and mental capacities are at about age 4-5. Possibly what I was looking for in his education would be different if that were different. Maybe I’d have made decisions that are more predictable to others. But he’s not, and I didn’t. Each advocate has to evaluate the data for him or herself. But take it from me: Moms can know best!

About Jane Thurston

Twitter •